The Tara Brooch is a prime example of early medieval Irish craftsmanship and Celtic art. Made from cast and gilt silver, its detailed design showcases the advanced metalworking skills of its creators.

Found in Bettystown, County Meath, in 1850, and later misattributed to the Hill of Tara to enhance its value, the brooch is a testament to the ingenuity and artistic sensibilities of the period. The Tara Brooch represents the pinnacle of Celtic art due to its complex design, exceptional craftsmanship, and the cultural significance embedded in its creation.

Similar to other national treasures like the Ardagh Chalice, the brooch features intricate patterns and symbols thought to provide protection.

Now housed in the National Museum of Ireland, the Tara Brooch is more than just jewelry. It symbolizes the high artistic achievements of early medieval Ireland and offers insights into the social and cultural context of the time.

The Significance of the Piece

Dating back to the 7th century AD, the Tara Brooch showcases the meticulous artistry and technical skill of its creators. Made from cast and gilt silver, it features intricate decorations on both sides, with interlacing patterns and detailed ornamentation. Discovered near Bettystown, Co. Meath, it highlights the advanced metalworking skills of the time.

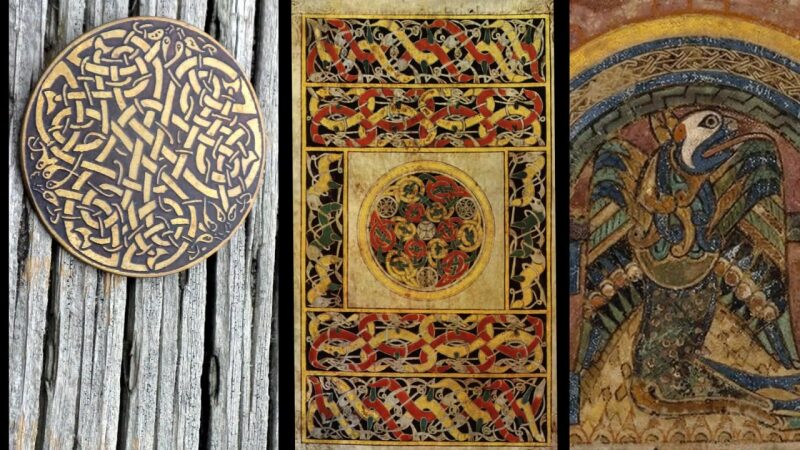

The brooch is a key piece of Ireland’s cultural heritage and is considered a pinnacle of early medieval Irish art, alongside the Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Paten. Its design, comparable to the Book of Kells, reflects the sophistication of Celtic art during Ireland’s “Golden Age.”

Beyond its beauty, the Tara Brooch offers insight into the social and cultural aspects of early Celtic society, emphasizing the importance of adornment and symbolism. It remains one of Ireland’s greatest treasures, valued for its artistic and historical significance.

History of the Brooch

The Tara Brooch’s name is misleading, as it has no connection to the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of the High King of Ireland. Instead, it was discovered in 1850 by two peasant boys on a beach 50 km north of Dublin, inside a tin box.

Skepticism surrounds this story since it’s unlikely a tin box would survive centuries on a beach. A more plausible version suggests the boys found it inland and concealed its true location to avoid landowner claims.

The boys’ mother took the brooch to an iron dealer who showed no interest. She then brought it to a watchmaker who, after cleaning and examining it, identified it as silver covered with gold filigree and bought it for 18 pence. The watchmaker soon sold it to Waterhouse Jewellers for twelve pounds.

During this time, the Celtic Revival was flourishing in Ireland, with a growing interest in Celtic art, songs, language, and traditions. George Waterhouse, owner of Waterhouse Jewellers, was a key figure in this movement. Recognizing a marketing opportunity, he renamed the brooch the Tara Brooch.

For 22 years, the Tara Brooch was the centerpiece of Waterhouse’s Dublin shop, attracting many visitors, including Queen Victoria, who requested it be sent to Windsor Castle for inspection. It was displayed at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, the Exposition Universelle in Paris, and an exhibition in Dublin in 1853, where the Queen viewed it again.

In 1872, the Royal Irish Academy acquired the Tara Brooch, which later became part of the National Museum of Ireland’s collection. Despite losing several gold panels over the years, its intricate beauty remains evident in the museum today.

Celts and Brooches

Brooches were common clothing accessories in Celtic times, used to fasten cloaks. They were large and sturdy, unlike today’s delicate versions, and worn by both men and women in different positions: at the shoulder for men and at the chest for women.

The pin always pointed upwards, and a law stated that if someone was injured by another’s pin, the owner was not at fault unless it protruded too far.

Initially, brooches were plain, but from 700-900 AD, beautifully decorated brooches made from precious metals became popular, worn by important figures in Celtic society, often clergymen, on special occasions.

Early Irish law required sons of major kings to wear gold brooches with crystal, while sons of minor kings wore silver. The Tara Brooch was likely made for a wealthy and almost certainly male individual.

Celtic brooches came in two styles: annular and penannular. Annular brooches formed a complete ring with a large pin.

Penannular brooches had a gap in the ring for the pin to move. In both styles, the ring was decorative and sat on top of the pin, which was pushed through the material and secured by slightly rotating the ring.

Celtic Art in Irish History

Celtic art originated in the Iron Age, characterized by intricate patterns, spirals, and knotwork. Early styles include Hallstatt and La Tène, known for detailed metalwork and geometric shapes.

With the La Tène culture around 500 BCE, artists refined their techniques, creating curvilinear forms in weaponry, jewelry, and everyday objects. This transition reflects increased sophistication and cultural interactions, especially with Greco-Roman influences.

In the early medieval period, Christian symbolism merged with traditional Celtic motifs. This fusion appears in illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells, combining religious themes with Celtic art. From 700 to 900 CE, Celtic art reached its peak, integrating native and external influences into a distinct aesthetic.

Celtic art is highly regarded in Irish history, symbolizing national identity and craftsmanship. The Tara Brooch, exemplifies this excellence, showcasing 8th-century metalworking skills with gold, silver, and amber in a pseudo-penannular design.

This blend of function and decoration is a hallmark of Celtic art, showing the culture’s ability to infuse beauty into practicality. These intricacies offer insights into the societal and cultural values of the time.