The legend of Hyperborea, a mythical land believed to have existed in the far north, has intrigued scholars for centuries.

Modern researchers continue to explore whether this ancient land ever truly existed and, if so, where it might have been located.

One of the most significant sources for this theory is the 1554 map by the famous cartographer Gerardus Mercator, who depicted Hyperborea as a landmass in the center of the Arctic Ocean.

But could this land have existed, or is it a creation based on ancient myths?

Above the Issedones… live the Arimaspians, one-eyed-men; above them dwell the gold-guarding griffins; and above the griffins, the Hyperboreans, whose land extends all the way to the sea. With the exception of the Hyperboreans, all these peoples, beginning with the Arimaspians, attacked their neighbours in successive waves. – In the Histories of the Greek writer Herodotus (c. 484 – 425/413 BCE)

Assumption 1: Mercator’s Map of Hyperborea is Accurate

According to the 1554 map, Hyperborea was situated at the center of the Arctic Sea, surrounded by mountains and divided by rivers into four large islands.

- Northern Europe

- Siberia

- Alaska

- Greenland

This similarity has led some to speculate that Hyperborea could have existed during the early Oligocene epoch, roughly 34 million years ago, when the continents had shapes similar to today’s but before the formation of large inland seas.

The theory suggests that Hyperborea could have existed up until the mid-to-late Miocene epoch, between 16 to 10 million years ago, when Arctic glaciation began.

If this map is correct, Hyperborea may have been a central landmass in the Arctic, surrounded by areas that are now part of northern Europe, Siberia, and Greenland.

However, this assumption requires that we accept Mercator’s map as an accurate depiction of Hyperborea.

Some scholars argue that this map was based on ancient sources that Mercator had access to, which may have either misrepresented or exaggerated the existence of this land.

Assumption 2: Mercator’s Map of Hyperborea is Inaccurate

If we assume that Mercator’s map is not accurate, we are left with a different puzzle.

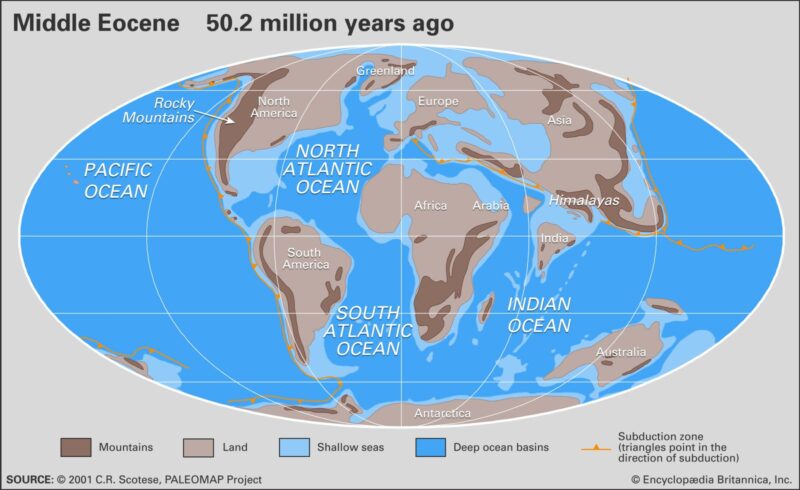

Geological and tectonic evidence suggests that there was, in fact, a significant landmass in the Arctic during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs (66 to 55 million years ago).

- Modern-day Greenland

- The Queen Elizabeth Islands

- Iceland

- Faroe Islands

- Parts of Scandinavia

- Northern Russia

Geological structures such as the Mendeleev and Lomonosov ridges, which stretch across the Arctic Ocean, may have connected this land to the Asian and European continents.

The map’s inaccuracies may stem from shifts in the Earth’s axis or Mercator’s reliance on ancient, incomplete data.

Nonetheless, during this time, Hyperborea could have been a vast, cold, but habitable land, separate from mainland North America by the Baffin and Labrador basins and bordered by shallow seas and land bridges to the west and east.

The Eocene Epoch

By the Eocene epoch, about 55 to 45 million years ago, the shape and geography of Hyperborea began to change.

The subsidence may explain why so much of the land that might have formed Hyperborea is now underwater.

At the same time, Scotland, Norway, and parts of northern Eurasia remained above sea level, indicating the presence of elevated areas in Hyperborea.

Interestingly, the fossil record from this time shows evidence of warm, subtropical climates in what is now the Arctic.

It suggests that the region was much warmer during the Eocene epoch, which fits with the idea that Hyperborea was once a temperate or even subtropical land.

Fossils of subtropical plants have been found on the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater ridge near the North Pole, further supporting this theory.

The Oligocene Epoch

During the Oligocene epoch, which began about 34 million years ago, the Greenland, Norwegian, and Lafontenskoy basins continued to subside, leading to the formation of deep seas that further fragmented Hyperborea.

By this time, the Greenland-Scotland Ridge, a critical land bridge, had been largely submerged, though parts of it remained above sea level. This gradual sinking of Hyperborea likely contributed to its eventual disappearance.

The rising sea levels and expanding Arctic basins reduced Hyperborea’s land area dramatically, shrinking it to a fraction of its original size.

The remaining fragments of Hyperborea were isolated in areas like Greenland, the Queen Elizabeth Islands, and parts of northern Europe.

By the time the Miocene epoch (16 to 10 million years ago) began, much of Hyperborea went beneath the Arctic Ocean, with only small portions remaining as isolated islands.

Hyperborea: A Myth or a Forgotten Continent?

Whether Hyperborea truly existed or not remains a mystery. The geological evidence supports the idea that a large landmass existed in the Arctic during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs, and this landmass could have been Hyperborea.

However, it is also possible that Mercator’s map was based on ancient myths and misunderstandings of the Arctic region’s geography. Some are even speculating that ancient India, with its pantheon of gods, was considered Hyberborea by ancient Greeks.

The shifting climates, geological changes, and glaciation that have occurred over millions of years make it difficult to determine the exact nature of Hyperborea.

But the tantalizing evidence from ancient maps, combined with modern geological research, suggests that there may be more to this legend than mere fantasy.

In the end, Hyperborea may have been a real, lost continent, now hidden beneath the Arctic ice, or it could be a symbol of humanity’s quest to understand the world’s most remote and mysterious regions.

Whether fact or fiction, the legend of Hyperborea continues to capture the imagination of explorers and scholars alike.